|

|

|

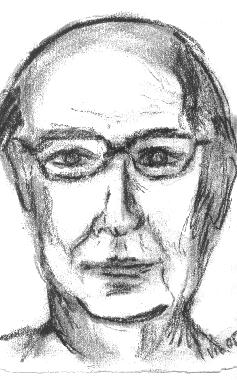

PHILIP LARKIN

Portratit by VIC (Cristina Ioana Vianu)

Essays on PHILIP LARKIN in

British Literary Desperadoes at the Turn of the Millennium, ALL Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999

The Desperado Age: British Literature at

the Start of the Third Millennium,

Bucharest University Press, 2004

A Restlessly Reticent Poet -- Philip Larkin (1922-1985)

Published in

LIDIA VIANU,

British Literary Desperadoes at the Turn of the Millennium, ALL Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999

Born in 1922, the year when the two stream of consciousness master works (Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land) were simultaneously published, after long years of elaborate shaping and reshaping, Philip Larkin is a typical representative of Desperado literature, the timorous literature of ‘everything has been tried, abandon all hopes of originality all ye who enter here.’ Which does not mean that Philip Larkin actually gave up striving for originality. Quite the reverse, he was even prouder of his novelty (peculiarity, at least) than his predecessors. Like all his Desperado fellows, he felt he was an independent and unique world, a poet who would not imitate and would never be imitated. Yet, he cherished his uniqueness in secret.

Unlike Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Alan Brownjohn and many others, Philip Larkin was a shy poetic voice, whose imaginings often ran wild, but whose words took a long time in ripening and acquiring poise. He wrote poetry, fiction and essays. He only published four volumes of verse. A 1965 Introduction to The North Ship (the revised edition) discloses the particular irony that tinges Philip Larkin’s reticence versus words. More often than not, this preeminently sensitive poet is unwilling to commit himself to literature. An interview with Peter Orr reveals him again as a high-strung poet, whose fondness of silence bursts from time to time, and then it gives birth to poems which are a constant source of amazement to the poet himself.

Let us remember T.S. Eliot’s feigned sense of disbelief and verbal insecurity, as compared to W.B. Yeats’ perfectly self-assured, overtly architectural poetry. Yeats was proud he was able to plan, to build a poem. He did not hide the efforts his mind made to arrest the right word, compose the music and engrave the thoughtful kernel. In early 20th century literature, the stream of T.S. Eliot’s consciousness is more devious. The author professes to withdraw, almost resign from office. If Yeats attempted to be an organized and conscious consciousness, his experimenting followers (Joyce, Woolf, Eliot) profess a kind of literary dizziness: their own projects catch them unawares. This secrecy conceals their laborious intentions, making their texts look like a stream of random associations. At the centre of this sometimes confusing web, the creative mind is richer than ever – a wealth of meanings and correlations, but infinitely more impatient than the traditional slow and sure architecture.

T.S. Eliot’s, Joyce’s impatience with the laziness of words, their inability to convey everything (the maze of all their possible meanings) at once could not be easily forgotten. Poetry still is confusing, jumping from one thought to another, without obvious connections between one statement and the following. The understatement, so lavishly used in the early twenties, is still eagerly preserved, even enhanced. Philip Larkin himself acknowledges T.S. Eliot as a major influence upon his making as a poet. His introduction to the revised edition of The North Ship clearly defines the mixture of styles besieging the twenty-three-year-old poet:

‘Looking back, I find in the poems not one abandoned self but several – the ex-schoolboy, for whom Auden was the only alternative to ‘old-fashioned’ poetry; the under-graduate, whose work a friend affably characterized as ‘Dylan Thomas, but you’ve a sentimentality that’s all your own’; and the immediately post-Oxford self, isolated in Shropshire with a complete Yeats stolen from the local girls’ school. This search for a style was merely one aspect of a general immaturity. It might be pleaded that the war years were a bad time to start writing poetry, but in fact the principal poets of the day – Eliot, Auden, Dylan Thomas, Betjeman – were all speaking out loud and clear...’

So, this is the mood which hovers about The North Ship (1945). The title-poem, ‘a legend,’ we are told, distorts the natural fall of stresses, in an almost Coleridge-like image:

I saw three ships go sailing by,

Over the sea, the lifting sea,

And the wind rose in the morning sky,

And one was rigged for a long journey.

Emily Dickinson looms in the distance. Three ships go out at sea. The east and the west-bound ships return. The North ship goes

wide and far

Into an unforgiving sea

Under a fire-spilling star,

And it was rigged for a long journey.

The words manage to shock us into following their flow with a certain interest, but, unfortunately, they can hardly alleviate the emotional burden the poet is encumbered with. Confusion consequently creeps in. Which is an understatement, since, as a matter of fact, the poetic image is so indirect that it may easily elude our understanding. Indirectness is the main quality of a good poem, of course, on one condition, though: it must be well-built, carefully planned so as to impress and haunt the reader. Careful indirectness turns the poem into an emblem of a thought or mood which the reader can share. In The North Ship, still groping and hardly waking up to the dawn of youthful lines, Larkin is careless. Music, memory, emotional waves, all carry him away. He contemplates the idea of death with the ignorance of a young body. The feigned sadness fails, the gravity is unconvincing. Death may look picturesque, but it is a long way off: it may not even exist, as far as young Larkin is concerned. He merely needs a theme to vent his need for sorrow, and he finds it there.

Despondency resorts to clarity, too. Larkin is, on the whole, a lover of prosaic clarity. He departs here from the path of Yeats, Auden, Eliot. Like many Desperado poets, in his better poems he refuses to use language as a code. There must be no barrier between his mood and his reader. Consequently, the words are commonplace, the sentences blankly correct. A blind poem which makes us see. Somebody with a ‘loveless’ heart wakes up and hears a cock crying far away, pulls back the curtains only to see the clouds that are too high up to reach, and decides that, in a strange way, everything, alive or lifeless, is alike. Sweet momentary emptiness that will in a second bump into boisterous joy. Dumb idleness, a poem calls it. The fire is extinguished, the glowing shadows die, a guest steps away into the windy street at midnight, and leaves behind ‘the instantaneous grief of being alone...’ Prolific plant, Larkin calls this aimless sorrow: and a very resourceful alliteration it is.

Blake, Byron, Tennyson, Eliot merge. The lines sound like other poets, the meaning is still frail. ‘My thoughts are children,’ a poem states. Which explains why the poems do not ripen yet. It rains over a darkening street, over Eliotian ‘stone places’ (which lose all connotations in the text), girls with troubled faces hurry along as if hurt, while the writing hand feels the heart ‘kneeling’ in its own ‘endless silence.’ There is however a certain taste for exhibited emotion, which makes this silence promising.

Gradually, the words take over more responsibility, the style grows steadier, less wavering, grasping the idea more firmly:

So every journey I begin foretells

A weariness of daybreak, spread

With carrion kisses, carrion farewells.

Morbidity is, or rather will be, replaced by hopelessness. Frailty is on its way towards becoming a poetic manner: the manner of a restlessly reticent poet. He looks helpless when names (love, death) besiege him, but we must not allow ourselves to be cheated: helplessness is his style, and he works patiently to find and refine it. An interesting stanza turns up to prove it:

I was sleeping and you woke me

To walk on the chilled shore

Of a night with no memory,

Till your voice forsook my ear

Till your two hands withdrew

And I was empty of tears,

On the edge of a bricked and streeted sea

And a cold hill of stars.

Larkin is learning the craft of concentration, the skill of multiple meanings merge into one remarkable image: a sea which is built in, its freedom surrounded by bricks and crossed by artificial streets. The ‘cold hill of stars’ which follows has nothing to do with the previous, highly suggestive line.

I read the remaining poems of this first volume hunting for interesting images – which means I already trust Larkin and expect them to come up any time now. It seems I am not mistaken, though they are not many yet: ‘a shell of sleep,’ ‘this season of unrest,’ ‘always is always now,’ ‘beyond the glass/ the colourless vial of day painlessly spilled.’

Ten years later, The Less Deceived (1955) came out. A title which applies to Larkin’s readers as well. Less deceived by picturesque despondency, we are ushered into a realm richer in incidents once experienced, closer to our own lives, more genuine, more enthralling. A photograph album shows the loved young girl under the colours of childhood. Photography is a ‘disappointing’ art, Larkin exclaims. Sorrow has turned into disappointment. The past has come on stage, as a new theme. Sadness is replaced by a simple pain, that we can understand. The poet’s soul races back to retrieve the lost years, then suddenly stops to contemplate itself. The poem is born:

In every sense empirically true!

Or is it just the past? Those flowers, that gate,

These misty parks and motors, lacerate

Simply by being over; you

Contract my heart by looking out of date.

The sentences flow naturally, as if uttered on music. Larkin carefully moulds the rhythm of his lines: slippery interruptions disturb the prosaic flow. The poet denounces himself as a character:

I, whose childhood

Is a forgotten boredom...

Eliot is at last left behind. A faithful, clear probing of privacy becomes Larkin’s main concern. It may already be an old trick for young Desperado poets, but back in the fifties it was definitely fresh. Ostentatious, yet blank confession is Larkin’s discovery (though not only his, of course). An X-ray of everyday life, clothed in everyday words.

The poems begin and end casually. The style is oral. This informal poetry may at first strike one as not being poetry at all. The abrupt end is discomfiting. No more plaintive rhymes. In the first volume, punctuation could not even be noticed, it was either overlooked or misused. Now it has earned its meaningful status. The statements, too, acquire the balanced rhythm of a mind thinking, of sensibility understood. A remarakable poem (Next, Please) makes new use of the North Ship, and this time we clearly understand the ‘black-sailed unfamiliar’ ship, ‘towing at her back/ A huge and birdless silence’ is the day when there is no ‘next, please,’ the end. The rhyme is used without irony, it wins back some of its lyrical force. No more Eliotian destructive refrain like ‘In the room the women come and go/ Talking of Michelangelo.’ Familiar and gentle, Larkin gives in to lyricism:

Always too eager for the future, we

Pick up bad habits of expectancy.

Something is always approaching; every day

Till then we say,

Watching from a bluff the tiny, clear,

Sparkling armada of promise draw near.

He also discovers now the theme of solitude. Larkin is everywhere a solitary poet, but his halo of loneliness is better noticed in this second volume, where he does not complain about it. The ‘cold heart’ was quite unconvincing. Devoid of emphasis, the lines strike gold. There is solitude beneath and beyond everything:

However we follow the printed directions of sex,

Despite the artful tensions of the calendar...

Larkin’s words grow bolder. Four-letter words are a poetic commonplace today. They were a hard conquest for Larkin. He brought himself to use them because they were part of, proof of genuine, everyday life. But we cannot help feeling him blush whenever he is bold. He is at his best when he stifles his pain in loneliness:

At once whatever happened starts receding.

Panting, and back on board, we line the rail

With trousers ripped, light wallets, and lips bleeding.

Yes, gone, thank God! Remembering each detail

We toss for half the night, but find next day

All’s Kodak-distant...

Self-pity has been left behind. It was much too direct and failed to impress. Now Larkin is rougher:

I detest my room,

Its specially-chosen junk,

The good books, the good bed,

And my life, in perfect order.

Triple Time is a poem as sharp as a knife. Our present is the dream of future of our childhood and our future is our failed past. The idea is more appealing than the words which clothe it. Overdoing toughness and informality, Larkin sometimes sprains his ankle by stepping outside the poem. He returns, however, with a deft line such as ‘where my childhood was unspent.’ It may sound like e. e. cummings, but it is so loaded with the verbal insignificance of the whole poem that it is far stronger. The rarer, the richer.

The Whitsun Weddings (1964), nine years later, is more self-assured. The poems abound in private meanings, and are somewhat less accessible, though not obscure. We find here a special narrative coherence of the volume, which characterizes Desperado poetry. This narrative coherence means that one has to read the whole volume in order to understand anything. Nowadays anthologies are very hard to make precisely because Desperado poets build a story within a volume. Each poem unfurls a further episode. Larkin, too, discovers this trick by means of which fiction steals into poetry. The reverse of what happened in the 1920s – when fiction was submerged by lyricism – is taking place. At the age of forty-two, Larkin brings out a volume of poems which somehow tell the story of his own life. He selects significant incidents and builds an atmosphere to be remembered. We may forget the poems, we will not forget the mood. One clever poem is Sunny Prestatyn. It makes free use of indecent words, but that does not seem to matter. ‘Come to Sunny Prestatyn’ is a decorous advertisement for some seaside resort. The image of a beautiful girl in the sand, against the background of palms and a hotel, is gradually defaced by passers by. Anonymous artists turn her into a snaggle-toothed, boss-eyed, moustached and pornographic image. Conclusion:

She was too good for this life.

A knife stabs her through in the end. The next day another poster is slapped up. Maybe those who found the sea, the sky and the young girl ludicrous will be satisfied:

Now Fight Cancer is there.

The instinct to destroy versus our own final destruction. No more to be said. Larkin is bitter now:

Strange to know nothing, never to be sure

Of what is true or right or real,

But forced to qualify or so I feel,

Or well, it does seem so:

Someone must know.

(...)

Even to wear such knowledge – for our flesh

Surrounds us with its own decisions –

And yet spend all our life on imprecisions,

That when we start to die

Have no idea why.

A wifeless, childless, loveless man, who will not go either backwards (into his past) or forward (towards nothingness) if he can help it, this is the hero of Larkin’s third volume of poetry. Larkin belittles this hero. His initial tenderness turns sour. The emptiness the first volume complained of was teeming with anticipation of what was too slow to arrive. This new emptiness looks final. We feel as if we had watched the first and last act of a play, but have missed the sentimental middle act. In short, we feel cheated. Even if the last line of the volume states that

What will survive of us is love,

we still feel scared by the blank stare of the last white page. Gentle Larkin is teaching us how to grow old.

Ten more years, and, at fifty-two, Larkin publishes High Windows (1974). In the New Statesman, the younger poet and critic Alan Brownjohn welcomed it:

‘Despite his disavowal of a poet’s obligation to develop, High Windows does show an indisputable development in Larkin (...). It’s doubtful whether a better book than High Windows will come out of the 1970s.’

It seems that, in one respect, Larkin did follow Eliot’s pattern: he did not print much. Out of the poems he printed, some may look commonplace if taken separately, yet each has a part to play in the volume as a whole. A sense of exhaustion, to which a growing bitterness is opposed, pervades everything. To the Sea blends present and past, memory and desire (to quote good old Eliot):

Still going on, all of it, still going on!

Walking along the shore, among children, parents and old people tasting their last summer. Instead of inspiring the sea, we take a deep breath of despair and go on.

The rhymes are sharpened to kill. The initial theme has come full circle. Apprehension has turned into much hated certainty (death):

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

Is it that they are born again

And we grow old? No, they die too.

Their yearly trick of looking new

(...)

Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

Childhood appears sadder and sadder to the ageing sensibility:

Like the wars and winters

Missing behind the windows

Of an opaque childhood...

Another world comes in sight. Seen out of high windows – which remind us of Eliot climbing the stairs in Ash Wednesday, III – youth rushes back into a wasted body, but finds it uninhabitable. The ageing eyes look upwards and the high windows disclose the ‘deep blue air,’ ‘nothing,’ ‘nowhere,’ ‘endless.’ Larkin tries his soul at Eliot’s assumed sense of acquired peace. The same poignancy results. Words (used as catharsis before) become useless. Speech refuses poetry. The poem refuses the poet. Here we stand, then, close to this poet at last: he has been banished out of his own words and moods, and we hold his hand, we share his despair.

Larkin’s despair soon becomes uncomfortable (like Eliot’s), very similar to Dylan Thomas’ ‘do not go gentle into that good night.’ The poet stares old age in the eye, and sees Yeats’ and Eliot’s deep fears merge: mouths gape open, ‘you keep pissing on yourself,’ nothing can stop the deterioration or make the body work again. ‘Why aren’t they screaming?’, Larkin chokes. The same as Emily Dickinson, he is at his best when he probes, almost pre-enacts death. All these lines are memorable. We knew death would come (young Larkin flirted with the thought in his early poetry), but then it

was all the time merging with a unique endeavour

To bring to bloom the million-petalled flower

Of being here.

Now, that it is almost here, we realize we should never have tarnished life with this apprehension, which is now too true. ‘How can they ignore it?’, Larkin screams again. The Old Fools sink back into the private reality of their own minds. They are there, not here. They are ‘baffled’ absences, unwillingly preparing to face what was once thoughtlessly imagined. Young imagination is as dangerous as ageing memory. Larkin’s poetry is mined. With High Windows, we look back and realize that we must tread it cautiously, carefully, fearing all the time that any innocent word may blow up the poem.

Old age is called by Larkin ‘inverted childhood.’ His whole poetry (like Eliot’s) is inverted, in a way. He grows more energetic and more fond of life, of a poetry of reality, as he grows older. What spurs him into writing well must be the same sense of loss which he was too young to communicate in his previous volumes. Now his powerlessness is perfect. He has experienced some of it at last. Having found something in his own life that he can write about, he strikes the right voice and no longer wavers. Eliot once said that Yeats was preeminently the poet of middle age. Following that pattern, Larkin is first and foremost the poet of the last age – an age which he was spared by an untimely death.

Bitterness reaches a climax. We look back longingly at Larkin’s early verse as we read:

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

In Joyce’s A Painful Case, James Duffy realizes when it is too late that he is ‘an outcast from life’s feast.’ So does Larkin.

A poet who wrote little, and published even less, Philip Larkin has nevertheless become a major voice in later 20th century British poetry. He best illustrates the transition from strong-willed experimenting (Eliot) to relaxed carelessness in poetry. He witnesses the slow withdrawal of lyricism from fiction and its reverse, the immersion of poetry into prose, or, rather, the creation of the Desperado poetic attitude: the disobeying of poetry. Like modern clothes, which can use any colour or cut as long as they are able to shock, Larkin felt free to look for his words everywhere. The hidden striving of his creation is to find a road of access to his innermost, real theme – the mood of the lonely, ageing man. Late found, this theme is not long dwelt upon. One last volume discloses its helpless despair. Speech needs no artifice, Larkin uses it as he finds it. Words cannot alleviate the painful poems of this poet who is unable to come to terms either with himself or with his poetry, restless but reticent to the bitter end.