|

|

|

Home Poets Novelists Critics Lidia Vianu Desperado Links Contact

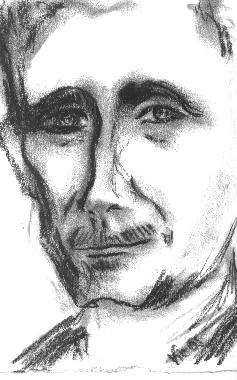

GEORGE ORWELL

Portratit by VIC (Cristina Ioana Vianu)

Essays on GEORGE ORWELL in

British Literary Desperadoes at the Turn of the Millennium, ALL Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999

The Desperado Age:

British Literature at the Start of the Third Millennium,

Bucharest University Press, 2004

LIDIA VIANU

Published in

LIDIA VIANU,

British Literary Desperadoes at the Turn of the Millennium, ALL Publishing House, Bucharest, 1999

George Orwell’s real name was Eric Blair. He was born in Bengal, and educated at Eton. He served in the Loyalist forces in the Spanish Civil War.

Orwell is a writer with a robot-like imagination and a fairly dry sensibility, which makes his plots look almost diabolical. He builds his novels by accumulation. He makes up images which convey, all of them, one major message: Beware of totalitarianism. The part he plays in 1984 is that of a stage manager who carefully puts together scenes, characters, lights, cues, in order to focus everything upon his thesis. Because of his monochord view, the novel ends by being very much like an exciting huge newspaper editorial written in small print. When I read it for the first time, in the 1970s, I was happy to find in it all the evils that surrounded me, named and described in detail. As Orwell’s own character, Winston Smith, puts it, I felt relieved to see my situation dissected and be able to read the results of the diagnosis illegally. It was as if attaching a name to the horrors, I could struggle free from them.

On rereading the novel in the 1990s, its novelty and cathartic function gone, I found it questionable as a piece of literature. It does not afford the pleasure of captured, re-enacted life. It is a long explanation of the nightmare some of us have actually lived. It is so accurate that it resembles more a list than a recording of incidents. Orwell’s imagination is matter-of-fact. He demonstrates by explaining, not by involving the reader emotionally.

1984 takes place in a future England, at the time of ‘Ingsoc’ (English socialism). The prophecy has not turned out to be true for England. The premises of Orwell’s dystopia – his knowledge of the Soviet Union and communism at the time - enable him to foresee the evolution of the totalitarian system in the countries where it took over. What seems obvious today, when most of these countries have struggled out of it and we can consequently talk freely about 1984, is that no advanced capitalist country outside the Russian sphere of influence could have joined it.

In contrast to Huxley’s world of comfort, leisure, affluence and well being, the image of Orwell’s future England (outlined sixteen years later than Huxley’s) is wretched. Poverty is a major theme, and it darkens everything. It is a poverty totally opposed to Huxley’s heaven of consumer goods. No sugar, not enough electricity, no coffee, no pans, no clothes, no chocolate. We know these things only too well. Only the most important members of the so-called inner Party have economic privileges, such as good cigarettes, wine, good coffee, good flats. There is one thing in abundance, however: the telescreen. The telescreen is a surveillance device and propaganda tool, as well. It exists everywhere, in every room. Everybody is watched, one is never alone, there is no privacy, the Party knows everything.

The constant fear of being seen or heard, betrayed by one’s own wife or even children, is so painful to us because we have experienced it until so recently. In Orwell it is exaggerated beyond everything bearable. He devises the word ‘thoughtcrime’, which means to rebel against the Party in your mind. Even that can be seen, from gestures, countenance, a whisper in one’s sleep. There even is such a thing as the Thought Police. Nothing is private. Just like Huxley, whose characters clamoured that everybody belonged to everybody else, Orwell’s heroes are doomed to belong to the Party.

The view is so drab that it renders even the reader helpless. People are like hopeless animals driven to work. While reading this book, you feel constantly on the verge of tears. They are tears of sadness for the wasted lives, of humiliation and, at last, of utter despair. The face of ‘Big Brother’, ‘the face of a man of about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and ruggedly handsome features,’ made to stare at you from whatever point you look at it, watches everyone all the time. Nobody has ever seen or heard Big Brother, he may as well be dead, but he is the chief of the Party and must be worshipped. All Party members have to wear identical blue overalls, to love Big Brother and hate fanatically the enemy Oceania is at war with (Eastasia or Eurasia, as it happens).

The telescreen in every room cannot be shut off completely, it can at best be dimmed. It registers everything, so you are never alone, you must always watch your face, your lips, your gestures, your thoughts. When Winston fails to keep up with the morning gymnastics on the screen (which sounds just like North Korea), he is promptly scolded. The absolute lack of privacy as seen by Orwell is just as maddening as that in Huxley, only it is more painful because it is experienced in such grim surroundings:

‘The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it; moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live – did live, from habit that became instinct – in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.’

Winston Smith, like Huxley’s savage John, reacts fiercely against this compelled dehumanization and decides to keep a diary. There is a dark recess in his room, where he thinks he cannot be spotted by the telescreen. He buys an old, beautiful notebook, and starts writing with difficulty. His mind finds it extremely hard to struggle free from fear, which fear, he now realizes, slowly destroys his intellect, prevents it from thinking.

Winston works most of the day (very often prolonged hours) for the Ministry of Truth – Minitruth, as it is called in Newspeak, the new, official language of Oceania. This Ministry of Truth is busy concealing reality, in fact. A huge number of people are busy rearranging old articles in old papers, in order to bring them up to date, to eliminate the contradictions between past and present statements. The memory of a whole nation is deliberately annihilated. We have come out of a communist regime and we know only too well how far lies can go. But we also know that Orwell exaggerates, that nobody can destroy man’s last refuge, his mind. Thoughts have been and will always be free. Communist countries did have a kind of Thought Police, though, in psychiatry hospitals sometimes. There the mind was tampered with until fear became so strong that it left the patient speechless.

In Oceania there are four Ministries, described as follows:

‘...the Ministry of Truth, which concerned itself with news, entertainment, education, and the fine arts; the Ministry of Peace, which concerned itself with war; the Ministry of Love, which maintained law and order; and the Ministry of Plenty, which was responsible for economic affairs. Their names, in Newspeak: Minitrue, Minipax, Miniluv, and Miniplenty.’

The description sounds depressing to anyone who has experienced these realities, whose names have nothing to do with what activities actually take place inside them. The virtue of lying is a major achievement. When Winston feels overwhelmed with the distortion of truth, he attempts the highest offence possible, he ‘opens’ a diary. He knows that any thoughts directed otherwise than towards the Party could bring him death or the forced labour camp. Yet, he starts writing on the 4th of April, 1984. It may be hard to remember what each of us was doing on that day. The only certain thing for which Winston can swear is that he is thirty-nine years old.

As we go along, accompanying him to destruction, we cross a land mainly inhabited by two groups: the Party members and the proles. The proles are unimportant. They are uneducated and even poorer than a common Party member. The hope that they might overthrow the system is absent. They are freer, though, and are not compelled to take part in the daily ‘Two Minutes Hate’, for instance, when everyone is supposed to prove fanatic loyalty to Big Brother. Emmanuel Goldstein is shown on the screen, as the Enemy of the People. He was once a Party leader, but betrayed it and disappeared. He is shown denouncing the dictatorship of the Party, demanding freedom of speech, freedom of the press and of thought, crying that the revolution has been betrayed. Reading all this, some feel how depressing it is to realize we have lived through all that and seem to be living it now all over again. History repeats itself.

The Thought Police unmasks spies and saboteurs every day. The oppressive atmosphere of this book reminds us only too well of our own world of lies until not long ago. It may not even be dead yet. Winston feels more and more crushed by the necessity to hide his thoughts, reactions, feelings, even to control his face. And when he fails to do so, when, just for once, he is honest with O’Brien (a colleague of the Inner Party), he makes a terrible mistake. Instead of a fellow conspirator against the Party, as Winston deems him to be, O’Brien turns out to be the man who tortures Winston in the end till utter annihilation. When, at the end of the book, Winston ceases to be himself, after prolonged torture and brain-washing at the hands of O’Brien and the Thought Police, we also lose all hope that any conspiracy (the so-called Brotherhood included) may exist within such a perfectly organized repressive system. In a way, we sigh with relief: this is, however, more than we have experienced.

The loneliness of the characters in Orwell’s book is more dehumanized than ours was. Yet it is not so very far away from it. Thoughtcrime is a fear that may have survived communism. So have the arrests that ‘invariably happened at night’. People disappeared at night – do they still? – , nobody came to know how or why, no trials, they were ‘vaporized’, and all their traces were lost.

A world teeming with secret agents, in which even children spy on and betray their own parents, as in the case of Winston’s neighbour, who shouts in his sleep ‘Down with Big Brother’, although he seems perfectly adapted to the system. His children denounce him, he is thrown in prison, and yet he is very proud of their education. His son, while playing, once shouted at Winston:

‘You’re a traitor! (...) You’re a thought-criminal! You’re a Eurasian spy! I’ll shoot you, I’ll vaporize you, I’ll send you to the salt mines!’

All children belong to the Organization called the Spies. They learn at a very tender age the ‘discipline of the Party.’ They frighten their parents. In school girls have sex-classes, during which they are taught that making love in order to bear children is their ‘duty’ towards the Party. Orwell is a master at creating images for lives wasted from the cradle to the grave.

In front of the slow death of the human brain, Winston takes refuge in his diary, which he hardly knows how to use. For whom does he write it? He has no idea:

‘To the future or to the past, to a time when thought is free, when men are different from one another and do not live alone – to a time when truth exists and what is done cannot be undone:

From the age of uniformity, from the age of solitude, from the age of Big Brother, from the age of double think – greetings!’

He works for the Party. He helps ‘control the past’ and promote doublethink, by changing all old articles in newspapers which are different from what the present states. His memory rebels against all this. His whole being reacts. His most manifest act of protest is falling in love with Julia. Feelings are not allowed. Marriages should be loveless. Besides, he is already married and merely separated, not divorced. Orwell’s model must have been the Stalinist society of the 1940s. Had he been a more subtle thinker or analyst, he would have felt that human beings never fail to find some refuge, some form of protest against dehumanization.

Winston begins by meeting Julia in a country spot. She is twenty-six and knows absolutely nothing about any other world than her own. Winston can at least think of the previous (capitalist) society, and even dreams of it, desperately wants to learn more. He clings to the past with the hope that it might come to pass again.

Later, they rent a small room in a prole district. They think they are safe there, but in the end it turns out later that everyone around was a spy. Even the mild-looking old man who gave them the room and sold Winston the copy-book for his diary. Even the small prole room, with ancient capitalist perfume, where they think there is no telescreen to spy on them, has a screen hidden behind a picture. Absolutely nothing is safe.

Both Winston and Julia are taken to prison and reformed beyond recognition. They meet again in the final pages, as two beings who have no life left, two robots who politely ignore each other. Orwell’s novel is a handbook of despair. Doris Lessing, for instance, took her psychological analysis to the utmost bearable limit: you could not split hairs or expose more than she does. Orwell goes to the outskirts of the nightmare.

Here, the question of the aesthetic value of their books arises. Doris Lessing is a good novelist, who passes the test of real literature. What about Orwell? Where can we place this essayistic, descriptive book? He enumerates evils and incidents. He does not venture inside a character, except to show it is empty, there is nothing alive in it. The plot is meagre, just a pretext to describe the surrounding world. He builds up a negative utopia, a dystopia, just like Huxley.

In many ways it is unfair to discuss the literary value of a dystopia. Orwell focuses upon building an essential image, a synthesis, like a definition of the totalitarian system. The literary ingredients he uses are meant to help us swallow his thoughts. His postmodernity mixes literature with journalism and political theory. He manages to arouse our deepest indignation and frustration. Had we not lived through most of what he describes, we would merely have been afraid. His atmosphere is haunting. As it is, we are saddened beyond speech. Saddened that his imagination, even as early as 1949, worked well, yet nobody in the communist countries had the power to do anything about it.

We could easily have been the heroes of this book, if the terror had continued. We had already started experiencing the loneliness, the fear, the poverty. Orwell may not have been a perfect novelist in 1984, but he was an accurate visionary. For the relief people encaged in communism felt when reading his book, for the sadness that part of our own life has been wasted so far, and for the faint hope that we may still see better times because we have emerged out of 1984 alive, Orwell is a writer who deserves our support at least, if no more.

1997